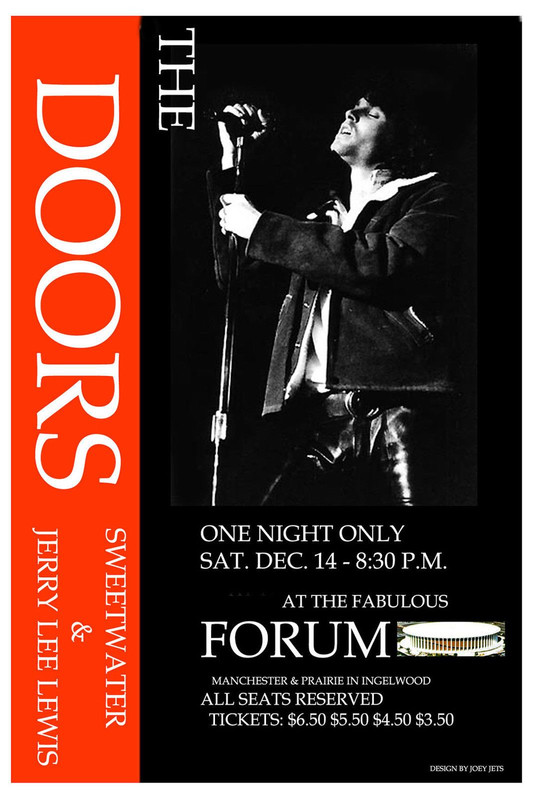

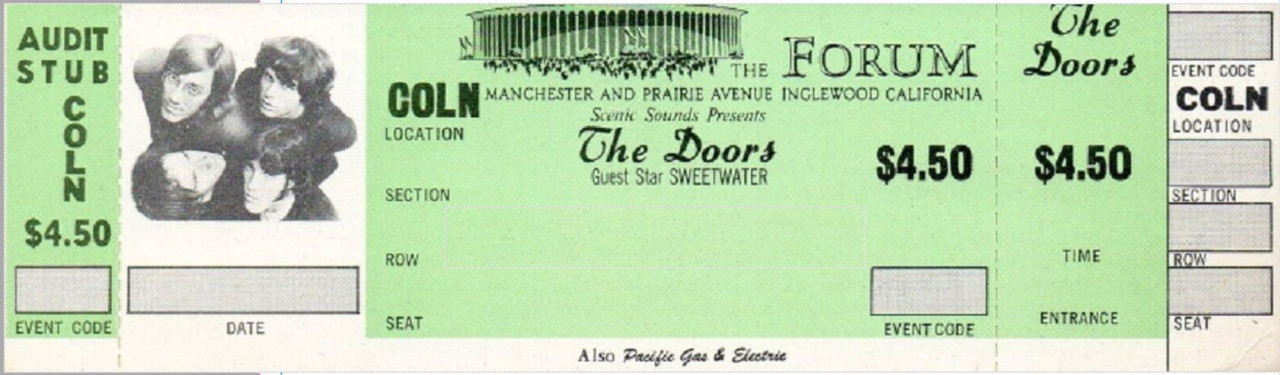

Saturday December 14 1968

Los Angeles Forum

Inglewood CA

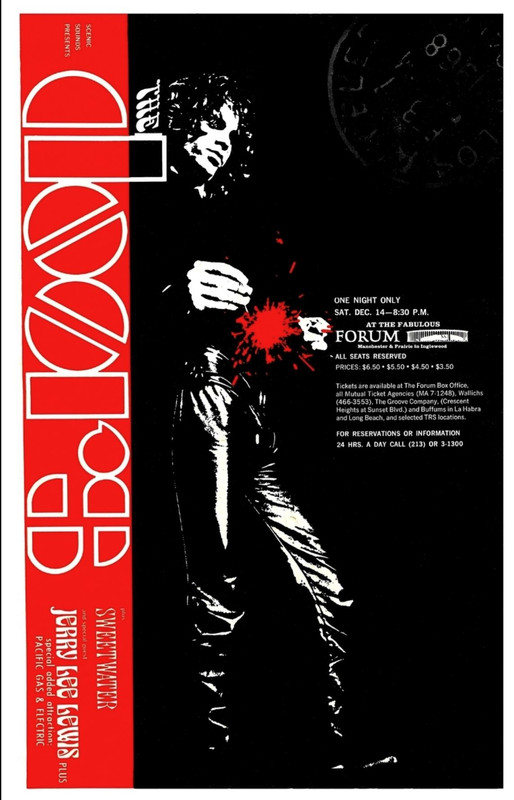

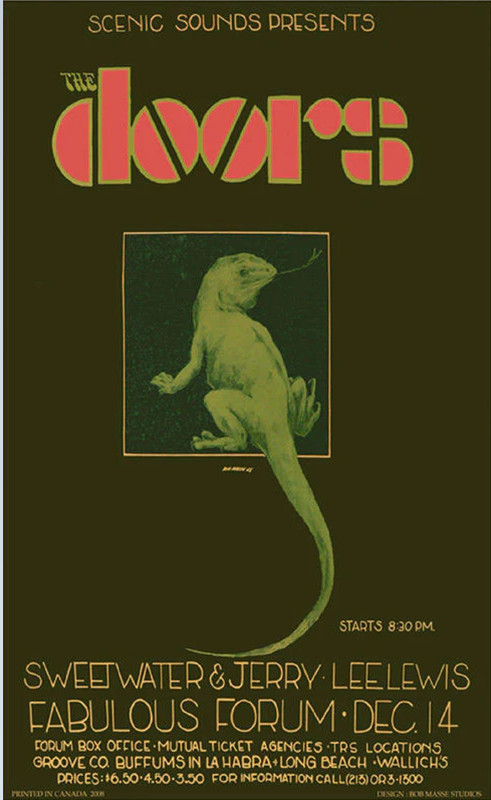

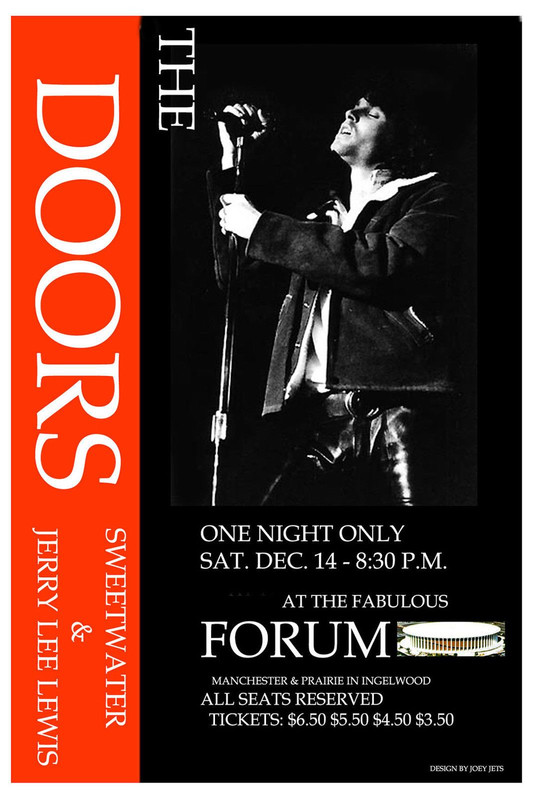

The 2nd poster put out to promote the concert

Providing a fitting end to their tremendously successful year on the outside and terrible year on the inside, The Doors fill the stage with 32 amplifiers, a string sextet, and a full brass section playing mostly new songs from The Soft Parade to a stunned audience of over 18,000 who only want to hear "Light My Fire". The audience has been booing every opening act horribly off the stage awaiting The Doors to sing their most popular songs. During their show, the band reluctantly gives in and plays "Light My Fire" but afterwards the audience begins chanting 'again, again'. They want The Doors to play the damn song again! Jim has all he can take and chastises the crowd.

Providing a fitting end to their tremendously successful year on the outside and terrible year on the inside, The Doors fill the stage with 32 amplifiers, a string sextet, and a full brass section playing mostly new songs from The Soft Parade to a stunned audience of over 18,000 who only want to hear "Light My Fire". The audience has been booing every opening act horribly off the stage awaiting The Doors to sing their most popular songs. During their show, the band reluctantly gives in and plays "Light My Fire" but afterwards the audience begins chanting 'again, again'. They want The Doors to play the damn song again! Jim has all he can take and chastises the crowd.

Only a year ago he was playing to at most 3,500 fans and had the control. Now, the crowds were beginning to call the shots and he is sick of it all. In defiance, in L.A., he walks to the front of the stage sits down and recites the entire 133 line Celebration of the Lizard in front of 18,000 - mostly teenagers! When it ends he glares at the audience, no words need spoken, and walks off the stage to almost no ovation. The backstage atmosphere is that of a funeral and later Jim plays kick the can with his brother Andy and Pam in the parking lot on the way home. Jim is becoming increasingly bummed out by audiences expectations of him. It will all culminate in a few months . . . . in Miami. Also performing but getting terribly booed off the stage: Jerry Lee Lewis, Sweetwater, Tzon Yen Luie (Japanese Koto player)

(Jim's brother Andy is in attendance)

"I don't know what will happen. I guess we'll continue like this for a while. Then to get our vitality back, maybe we'll have to get out of the whole business. Maybe we'll all go to an island by ourselves and start creating again."

Jim Morrison interviewed the afternoon of the Forum show.The Doors - Tell All The People (Audio) Forum 1968

The Doors: Can They Still "Light My Fire"? "Play 'Light My Fire’" "Yeah, ‘Light My Fire.’" Out of the vastness of the Los Angeles Forum, its 18,000 seats filled on a December Saturday night with the cream of LA’s teeniebopper set, came the insolent cry. The Doors didn’t want to do their 1967 hit; not only had they just finished their first number, but on stage with them and their thirty-two amplifiers were a string sextet and a brass section ready to perform new Doors music.

They got through a few more numbers, but then with the yelling getting louder, they acquiesced. A roar of cheers and instantly the arena was a glow with sparklers lit in literal tribute. The song over, and the kids shouting for one more once, lead singer Jim Morrison, in a loose black shirt and clinging black leather pants, came to the edge of the stage.

"Hey, man," he said, his voice booming from the speakers on the ceiling. "Cut out that shit." The crowd giggled.

"What are you all doing here?" he went on. No response.

"You want music?" A rousing yeah.

"Well, man, we can play music all night, but that’s not what you really want, you want something more, something greater than you’ve ever seen, right?"

"We want Mick Jagger," someone shouted. "‘Light My Fire,’" said someone else to laughter.

It was a direct affront, but the Doors hadn’t seen it coming. That afternoon before the concert Morrison had said, "We’re into what these kids are into." Driving home from rehearsal in his Mustang Shelby Cobra GT 500, he swept his arm wide to take in the low houses that stretched miles from the freeway to the Hollywood Hills. "We’re into LA. Here kids live more freely and more powerfully than anywhere else, but it’s also where old people come to die. Kids know both and we express both."

The teens had belonged to the Doors; their amalgam of sensuality and asceticism, mysticism and machine-like power had won these lushly beautifully children heart and soul, and the kids had made them the biggest Anerican group in rock music. Now, at one of their biggest concerts, prelude to the biggest ever at New York’s Madison Square Garden in January, the kids dared laugh, even at Morrison. Not much, but they had begun.

The Doors started out in LA’s early hip scene in 1965. Morrison, then 22, son of a high-ranking Navy official, met organist-pianist Ray Manzarek on the beach at Santa Monica while were both making experimental films at UCLA. Drummer John Densmore and guitarist Robby Krieger became friends of Manzarek’s at one of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s first meditation centers in Southern California. Named from a line of Morrison’s poetry — "There are things that are known and things that are unknown; in between are doors" — by early 1966 they had their first date, playing for $35 a week at a tiny and now defunct club on Sunset Strip.

While on their second job as the house band at the Whisky a Go Go, working behind dozens of groups they have now eclipsed, they began to build a following, playing blues and classic rock songs with a harsh and eerie stringency. "We were creating our music, ourselves, every night," Morrison said, "starting with a few outlines, maybe a few words for a song that gradually accrued particles of meaning and movement. Sometimes we worked out in Venice, looking at the surf. We were together and it was good times."

Their best songs, 'Crystal Ship', the diabolical 'The End' and 'Light My Fire' took shape in those early days while Morrison was developing the erotic style that has made him the group’s star and rock’s biggst sex symbol. He doesn’t fall off stages any more, but he writhes against the microphone stand, leaps from eyes-closed passivity into shrieking aggression, and moans sweet pain like a modern St. Sebastian pierced by the arrows of angst and revelation.

Just about everybody takes him seriously: the New Haven police who last year arrested him for "giving an indecent or immoral exhibition"; the girls who rush the stage, sometimes only to get ashes flicked from his cigarette; and critics who reave in detail about "rock as ritual." But no one takes Morrison as seriously as Morrison takes Morrison.

His stage manner, he said, unlike the acts of Elvis, Otis Redding, and Mick Jagger, with whom he is often compared, has a conscious purpose. Shyly, almost sleepily soft-spoken in private, he sees his public self as a new kind of poet-politician. "I’m not a new Elvis, though he’s my second favorite singer — Frank Sinatra is first. I just think I’m lucky I’ve found a perfect medium to express myself in," he said during a rehearsal break, slouched tiredly in one of the Forum’s violently orange seats. Though handsome with his pale green eyes and Renaissance prince hair, he has none of the decadent power captured in the spotlight.

"Music, writing, theatre, action — I’m doing all those things. I like to write, I’m even publishing a book of my poems pretty soon, stuff I had that I realised wasn’t for music. But songs are special. I find that music liberates my imagination. When I sing my songs in public, that’s a dramatic act, not just acting as in theater, but a social act, real action.

"Maybe you could call us erotic politicians. We’re a rock ‘n’ roll band, a blues band, just a band, but that’s not all. A Doors concert is a public meeting called by us for a special kind of dramatic discussion and entertainment. When we perform, we’re participating in the creation of a world, and we celebrate that creation with the audience. It becomes the sculpture of bodies in action.

"That’s politics, but our power is sexual. We make concerts sexual politics. The sex starts out with just me, then moves out to include the charmed circle of musicians on stage. The music we make goes out to the audience and interacts with them, they go home and interact with the rest of reality, then I get it back by interacting with that reality, so the whole sex thing works out to be one big ball of fire."

That analytical abandon was just right for the serious rock of the post Sgt Pepper era. After the album version of 'Light My Fire' got heavy airplay on FM rock stations, Elektra released a shorter single that became a Top-40 number one. The Doors have followed it with a series of singles and two more albums. They have a quickly identifiable instrumental sound based on blues topped with Morrison’s strong voice and lyrics. Manzarek plays a rather dry organ, but Krieger is an aggressive guitarist and Densmore a solid and inventive drummer.

Yet as the kids in the Forum knew, they’ve never topped 'Light My Fire'. The abandon has gotten more and more cerebral, the demonic pose more strained. The new music they wanted the crowd to like at the concert was abstract noise crashing behind a Morrison poem of mandering verbosity.

After the show Morrison said it had been "great fun," but the backstage party had a funereal air. And at times that afternoon, he showed that he knew their first rush of energy was running out. Success, he said, looking beat in the orange chair, had been nice. "When we had to carry our own equipment everywhere, we had no time to be creative. Now we can focus our energies more intensely."

He squirmed a bit. "The trouble is that now we don’t see much of each other. We’re big time, we go on tours, record, and in our free time, everybody splits off into their own scenes. When we record, we have to get all our ideas then, we can’t build them night after night like the club days. In the studio creation is not so natural.

"I don’t know what will happen. I guess we’ll continue like this for a while. Then to get our vitality back, maybe we’ll have to get out of the whole business. Maybe we’ll all go off to an island by ourselves and start creating again."

New York Times December 1968 Michael LydonDOORS PLAY AT HOLLYWOOD BOWLThe Doors concert at the Hollywood Bowl Friday night should have been an exciting event, the high point of the career of a local rock quartet whose struggle for success has taken more than two years. Instead it was a bore, the most disappointing pop concert at the Bowl since the Jefferson Airplane and an ill mannered audience made a shambles of the place last summer.

Again, the audience was largely to blame, but much of the fault lies with The Doors, particularity lead singer Jim Morrison for failing to gain a rapport with the crowd.

There are a number of factors which may have contributed to the lack of success of the appearance. The date was July 5 and there were firecrackers left over from the previous day, so the evening was punctuated with detonations and pyrotechnics from self appointed entertainers in the audience.

Some agile outsiders scaled the walls of the Bowl and gained momentary notoriety as squads of ushers – those who weren’t antagonizing the fireworks people into further displays – converged on them. A covey of photographers lapped at the foot of the stage and wandered around the quartet, oblivious to the audience.

So much for the distractions with which The Doors had to compete. A sizable part of the capacity crowd did not seem interested in seeing them, a lack of enthusiasm which manifested itself in random yells and myriad conversations during most of their set. Whey were these people there? Neither of the other two groups on the bill – the Chambers Brother and Steppenwolf – has had a local hit yet, so it is doubtful that they attracted a significant number of anti-Doors followers to the event.

What Could They Lose?

Part of the problem may be that the concert was sponsored by radio station KHJ (an irony, since the Top 40 operation has been reluctant until recently to play The Doors’ records; they once even eliminated the group from their playlist). Some of their listeners, presumably, came out of curiosity. It was sponsored by their favorite station, they had heard three of the groups records – “Light My Fire,” “The Unknown Soldier” and “Hello I Love You” – and what could they lose?

Even against the distractions and the curiously mixed audience, though, The Doors should have succeeded. The Chambers Brothers, who preceded them, were a great successes, particularly with their “Time Has Come Today,” which roused part of the audience into a standing ovation. Steppenwolf, however, met a colder fate than The Doors with a set which dragged despite it’s brevity.

The pacing of The Doors’ performance seemed wrong, at least wrong for that setting and that crowd. Morrison began with “When The Music’s Over,” a long dramatic number dotted with soft interludes. Shouts from the audience pierced the quiet passages and the mood of the song. Next came “Alabama Song,” which flowed into “Back Door Man,” then a couple of Morrison’s morbid surrealistic narratives and then “Hello I Love You,” the first song which a non album buying KHJ listener would have recognized. This sequence, however, has worked well for The Doors in other concert situations.

Detached and Mildly Amused

Morrison seemed detached and subdued and mildly amused during The Doors’ set, too good humored to work into the catatonic state which characterizes his most hypnotic and frightening performances. Even such potentially scary bits as his recitation during “The End” of his desire to die in a field where the birds could pluck out his eyes, the snakes could suck on him and the worms could eat him came off as ridiculous pose.

Fifty two amplifier speaker combinations (7,000 watts of power according to one of the emcees) filled the Bowl with Jim Morrison’s voice and the sounds of Ray Manzarek on organ; Robby Krieger on guitar and Jim Densmore on drums. The sound potential of such an array of amplification is enormous but it somehow lacked the punch they achieve indoors. Everything was audible, including a comic burp by Morrison in response to some heckling, but the music had little impact.

Three of the numbers, “Hello I Love You,” “The Unknown Soldier,” and “Spanish Caravan” were taken from their album, “Waiting For The Sun,” which will be released on Elektra within the next two weeks. Other tunes from the album include, “Yes, The River Knows,” “Love Street,” “Summer’s Almost Gone,” “My Wild Love,” “Not To Touch The Earth,” “We Could Be So Good Together,” “Five To One” and “Wintertime Love.”

The LP is gentler and more romantic than their previous two albums and Morrison’s voice sounds better than it has before. An advance listening in a congenial setting – not the best situation in which to judge a record, since the enthusiasm of others can be contagious – left me convinced that it is their best album. The Bowl appearance, however, was far from their best.

Los Angeles Times July 8 1968 By Pete JohnsonThe Doors At The Forum

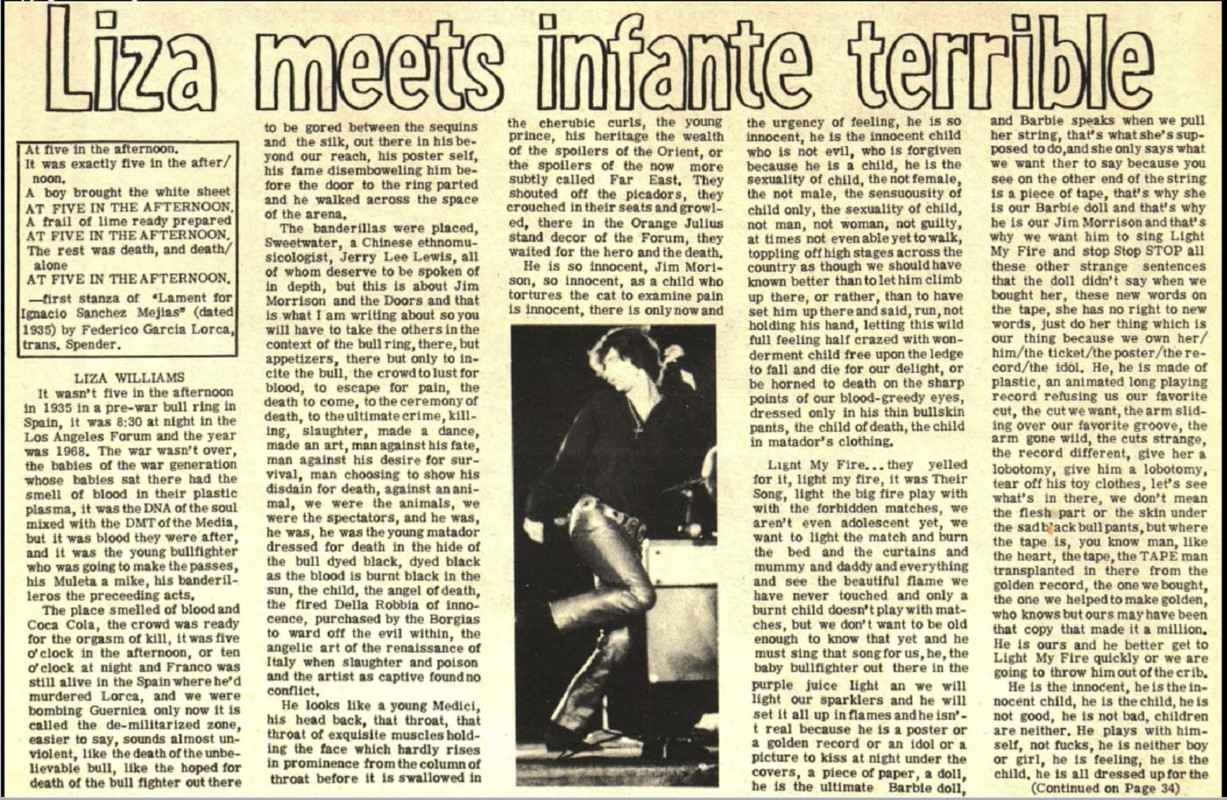

Morrison: The Ultimate Barbie DollHe looks like a young Medici, his head back, that throat, that throat of exquisite muscles holding the face which hardly rises in prominence from the column of throat before it is swallowed in the cherubic curls, the young prince, his heritage the wealth of the spoilers of the Orient, or the spoilers of the now more subtly called Far East. They shouted off the picadors, they crouched in their seats and growled, there in the Orange Julius stand décor of the Forum, they waited for the hero and the death.

He is so innocent, Jim Morrison, so innocent as a child who tortures the cat to examine the pain is innocent; there is only now and the urgency of feeling. He is so innocent, he is the innocent child, he is the sexuality of child, not female, the not male, the sensuality of child only, the sexuality of child, not man, not woman, not guilty, at times not even able yet to walk, toppling off high stages across the country as though we should have known better than to let him climb up there, or rather, than to have set him up there and said, run, not holding his hand, letting this wild full feeling half crazed with wonderment child free upon the ledge to fall and die for our delight, or be horned to death on the sharp points of our blood greedy eyes, dressed only in his thin bull skin pants, the child of death, the child in matador’s clothing.

“Light My Fire,” they yelled for it, light my fire, it was Their Song, light the big fire, play with the forbidden matches, we aren’t even adolescent yet, we want to light the match and burn the bed and the curtains and mummy and daddy and everything and see the beautiful flame we have never touched and only a burned child doesn’t play with matches, but we don’t want to be old enough to know that yet and he must sing that song for us, he , the baby bullfighter out there in the purple juice light and we will light our sparklers and he will set it up in flames and he isn’t real because he is a poster or a golden record or an idol or a picture to kiss at night under the covers, a piece of paper, a doll, he is the ultimate Barbie doll, and Barbie speaks when we pull her string, that’s what we want her to say because you see on the other end of the string is a piece of tape, that’s why she is our Barbie doll and that’s why he is our Jim Morrison and that why we want him to sing “Light My Fire” and stop STOP all these other strange sentences that the doll didn’t say when we bought her, these new words on the tape, she no right to new words, just do her thing which is our thing because we own her/him/the ticket/the poster/the record/the idol. He, he is made of plastic, an animated long playing record refusing us our favorite cut, the cut we want, the arm sliding over our favorite groove, the arm gone wild, the cuts strange, the record different, give her a lobotomy, give him a lobotomy, tear off his toy clothes, let’s see what’s in there, we don’t mean the flesh part under the sad black bull pants, but where the tape is, you know man, like the heart, the tape, the TAPE, man, transplanted in there from the golden record, the one we bought, the one we helped to make golden – who knows but ours may have been that copy that made it a million. He is ours and he better get to “Light My Fire” quickly or we are going to throw him out of the crib.

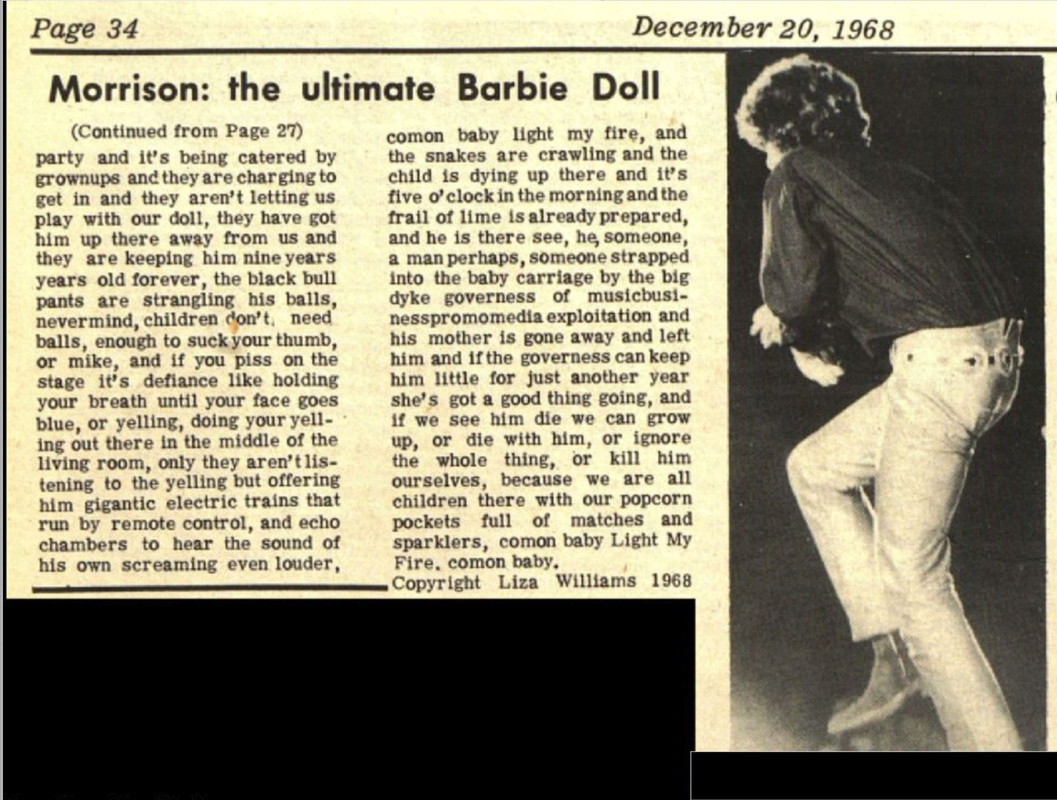

He is innocent, he is the innocent child, he is the child, he is not good, he is not bad, children are neither. He plays with himself, not fucks, he is neither boy nor girl, he is feeling, he is the child. He is all dressed up for the party, and it’s being catered by grownups and they are charging to get in, and they aren’t letting us play with our doll, they have got him up there away from us and they are keeping him nine years old forever, the black bull pants are strangling his balls, never mind, children don’t need balls, enough to suck your thumb, or mike, and if you piss on the stage, it’s defiance like holding your breath until your face goes blue, or yelling, doing your yelling out there in the middle of the living room, only they aren’t listening to the yelling but offering him gigantic electric trains that run by remote control, and echo chambers to hear the sound of his own screaming even louder, com’ on baby light my fire, and the snakes are crawling and the child is dying up there and it’s five o’clock in the morning and the trail of lime and salt is already prepared, and he is there, see, he, someone, a man perhaps, someone strapped in the baby carriage by the big dyke governess of music business promo media exploitation and his mother is gone away and left him and if the governess can keep him little for just another year she’s got a good thing going, and if we can see him die we can grow up, or die with him, or ignore the whole thing, or kill him ourselves, because we are all children there with our popcorn pockets full of matches and sparklers, com’ on baby Light My Fire, com’on baby.

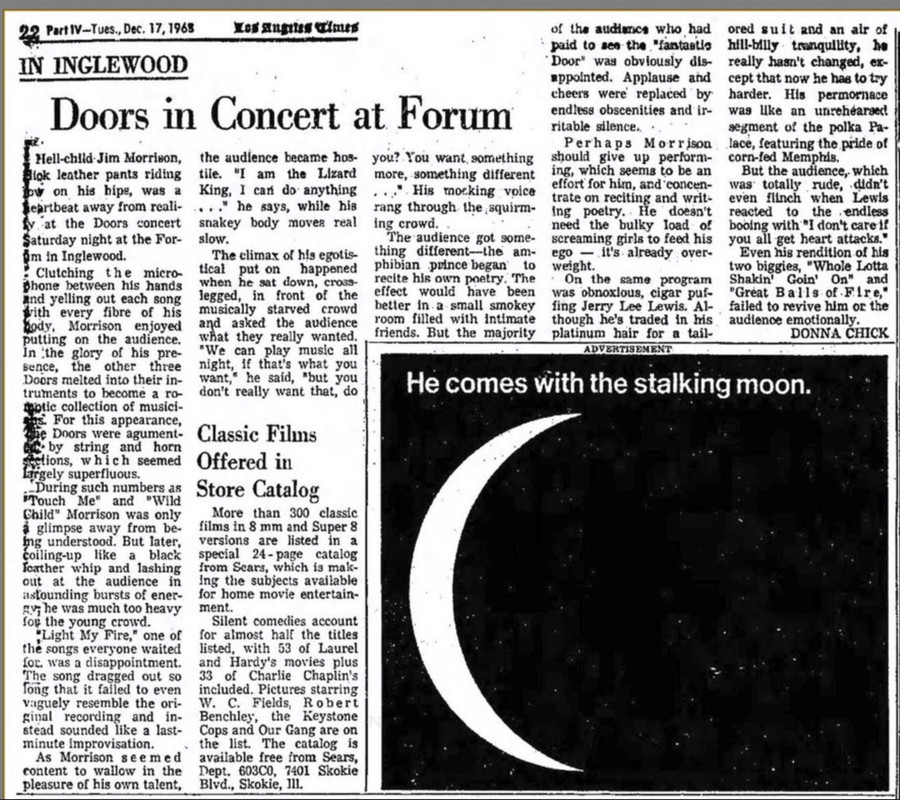

Los Angeles Free Press By Liza WilliamsIn Inglewood

December 17 1968

Doors In Concert At ForumHell-child Jim Morrison, black leather pants riding low on his hips, was a heartbeat away from reality at the Doors concert Saturday night at the Forum in Inglewood.

Clutching the microphone between his hands with every fibre of his body, Morrison enjoyed putting on the audience. In the glory of his presence, the other three Doors melted into their instruments to become one romantic collection of musicians. For this appearance, The Doors were augmented by string and horn sections, which seemed largely superfluous.

During such numbers as “Touch Me” and “Wild Child,” Morrison was only a glimpse away from being understood. But later, coiling up like a black leather whip and lashing out at the audience in astounding bursts of energy he was much too heavy for the young crowd.

“Light My Fire,” one of the songs everyone waited for was a disappointment. The song dragged out so long that it failed to even vaguely resemble the original recording and instead sounded like a last minute improvisation.

As Morrison seemed content to wallow in the pleasure of his own talent, the audience became hostile. “I am the Lizard King, I can do anything…” he says, while his snaky body moves real slow.

The climax of his egotistical put on happened when he sat down, cross legged, in front of the musically starved crowd and asked the audience what they really wanted. “We can play music all night, if that’s what you want,’ he said, “but you don’t really want that, do you? You want something more, something different…” His mocking voice rang through the squirming crowd.

The audience got something different – the amphibian prince began to recite his own poetry. The effect would have been better in a small smokey room filled with intimate friends. But the majority of the audience who had paid to see ‘the fantastic Door’ was obviously disappointed. Applause and cheers were replaced by endless obscenities and irritable silence.

Perhaps Morrison should give up performing, which seems to be an effort for him, and concentrate on reciting and writing poetry. He doesn’t need the bulky load of screaming girls to feed his ego – it’s already over weight.

On the same program was obnoxious, cigar puffing Jerry Lee Lewis. Although he’s traded in his platinum hair for a tailored suit and an air of hillbilly tranquility, he really hasn’t changed, except that now he has to try harder. His performance was like an unrehearsed segment of the Polka Palace, featuring the pride of corn fed Memphis.

But the audience which was totally rude, didn’t even flinch when Lewis reacted to the endless booing with “I don’t care if you all get heart attacks.”

Even his rendition of his two biggies, “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” and “Great Balls Of Fire,” failed to revive him or the audience emotionally.

Los Angeles Times By Donna Chick