Post by darkstar on Jan 20, 2005 20:02:58 GMT

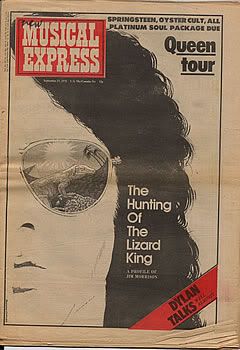

The Hunting Of The Lizard King by Mick Farren

September 27 and October 4 1975

New Musical Express

I only saw Jim Morrison twice.

Each time, even off stage, he gave the appearance of a

man performing his own private movie. Maybe in some

secluded place he was able to drop the self-inflicted

role; maybe the Morrison movie occupied his waking

hours.

Certainly all the evidence shows that while there was even

one person around to watch, Morrison performed. The

first time I was him was at the Roundhouse. It was a

Middle Earth all-night spectacular that starred the

Doors and the Jefferson Airplane - the most ambitious

project yet tackled by the flower punks and the

psychedelic wheeler-dealers who rode herd on what was

laughingly called London's underground rock

business.

It was clear right from the first that there was no

love lost been the Doors and the Airplane. In the

first wave of back-stage gossip came the news that a

high-level tactical battle had been raging all afternoon

over who should go on first. The Doors had won - by

the strategic use of stage lighting. Their roadies

had arranged the Doors' 20-odd Acoustic speakers,

meticulously matched black, rexine-covered monoliths crowned

by baby-blue high frequency horn, like the pillars

at a Nuremburg rally. The Airplane had little

choice, with their somewhat ragbag assortment of

hippie-built cabinets, to work around the Doors' fait accompi.

Both bands had obviously approached the London concert

determined to emerge as The Stars. The Airplane had brought

the entire Joshua Light Show from the Fillmore West.

The Doors simply had Jim. They did, however, have one

other advantage. Granada TV was making a film of the

Doors and Granada TV's money was intrumental in the

staging of the show. This was the Doors ultimate answer.

If anyone didn't give them what they wanted, they

could cause a great deal of trouble.

It was typical of Morrison's public personna that, as the Doors

performance got under way, he slowly began to turn on the

camera crew. At first he posed for the three big

cumbersome outside broadcast cameras, then his narcissism

started to plunge over the edge. He dodged them nimbly,

jumping out of range each time they tried to focus on

him. Finally, with a grand gesture of childish

petulance, he flung out a dramatic arm and demanded the TV

lights should be shut off. He pulled the audience in

behind as he warmed to the role of the star punk giving

the finger to the old folks' medium. A storm of

catcalls and booing broke out. The lights were finally

extingished, and the rest of the film had to be shot in murky

half darkness.

During the second performance Morrison went a stage further. He

actually turned on the audience, interrupting the music with a

stream of random obsenities until it seemed that he produced what he

considered a postive reaction from the crowd. Once that was

achieved, he got back to business as usual. It was then

that the idea first occured to me that there was

something inside Morrison that forced him to push any

relationship to the ultimate. With both individuals and

audience he appeared to need to see how much they could

take. To define, by practical experiment, how much

abuse anyone would put up with before they ceased to

adore him. It was this willingness to go to the limit

that set Morrison apart from the commond herd of

posing, macho rock frontmen. It also created what was

possibly the greatest problem. As he discovered the

depth's of public masochism, just how much abuse these

people were willing to accept without revolting, he

became disgusted.

The second time I saw Jim Morrison it became

clear that his major victim was himself. It was

backstage at the Isle Of Wight Festival. He looked a mess.

A full beard and a cossack style smock couldn't

disguise the fact that he was grossly overweight. He had

been herded into a corner by John Sebastian and was

clutching a brandy, grunting responses, and looking for a

way to escape the tie-dyed collection of platitudes

as Sebastian gushed on about how "far out it all

was." Morrison looked desperate. Not just to get away

from the current situation. He seemed to have the

desperation of someone who knows his control is slipping

away.

The feeling was reinforced when he came out on the

stage. He was a shamling parody of himself. It was as

though he knew his performance wasn't worthy of the huge

crowds ritual adulation, that if they applauded so

easily their devotion could only be worthy of

contempt.

Over the years the memory becomes shaky. I can't quite

remember if Jimi Hendrix followed the Doors or the Doors

followed Hendrix. I was certainly drunk. Two things are

clear, however, they both played during the evening,

when the campfires of that particularily strife-torn

festival blazed across the hillside. They both play badly,

by their own standards, and they both seemed

sickened when the crowd received a medicore set as though

it was a triumph. In a matter of months, both men

were dead.

JAMES JAMES MORRISON MORRISON

COMMONLY KNOW AS JIM.

In the Jim Morrison Story, whom

would they get to play Jim as a boy? Whom for that

matter would they get to play Jim as a man? In the

magazine story there is hardly enough space for the

interviews with old school chums. That has o be left to He

Who Writes The Book. The Morrison early life has to

be presented as one of those continous dissolve

montages, like the News on the March sequence from "Citizen

Kane." No sooner has one scene appeared before it

dissolves for the next.

It's a boy, Mrs. Morrison, it's

a boy. The baby cradled by proud parents, mother

adoring, father dignified by gold braid. The child grows

into a sensitive, large eyed Freddy Bartholomew kind

of brat with dark curly hair. We see him playing

baseball, running through the fields. The picture darkens.

He gazes pensively at the rain on the window. Fights

with father, confrontation, running again, this time

through the rain. This isn't joy, now it's

flight.

September 27 and October 4 1975

New Musical Express

I only saw Jim Morrison twice.

Each time, even off stage, he gave the appearance of a

man performing his own private movie. Maybe in some

secluded place he was able to drop the self-inflicted

role; maybe the Morrison movie occupied his waking

hours.

Certainly all the evidence shows that while there was even

one person around to watch, Morrison performed. The

first time I was him was at the Roundhouse. It was a

Middle Earth all-night spectacular that starred the

Doors and the Jefferson Airplane - the most ambitious

project yet tackled by the flower punks and the

psychedelic wheeler-dealers who rode herd on what was

laughingly called London's underground rock

business.

It was clear right from the first that there was no

love lost been the Doors and the Airplane. In the

first wave of back-stage gossip came the news that a

high-level tactical battle had been raging all afternoon

over who should go on first. The Doors had won - by

the strategic use of stage lighting. Their roadies

had arranged the Doors' 20-odd Acoustic speakers,

meticulously matched black, rexine-covered monoliths crowned

by baby-blue high frequency horn, like the pillars

at a Nuremburg rally. The Airplane had little

choice, with their somewhat ragbag assortment of

hippie-built cabinets, to work around the Doors' fait accompi.

Both bands had obviously approached the London concert

determined to emerge as The Stars. The Airplane had brought

the entire Joshua Light Show from the Fillmore West.

The Doors simply had Jim. They did, however, have one

other advantage. Granada TV was making a film of the

Doors and Granada TV's money was intrumental in the

staging of the show. This was the Doors ultimate answer.

If anyone didn't give them what they wanted, they

could cause a great deal of trouble.

It was typical of Morrison's public personna that, as the Doors

performance got under way, he slowly began to turn on the

camera crew. At first he posed for the three big

cumbersome outside broadcast cameras, then his narcissism

started to plunge over the edge. He dodged them nimbly,

jumping out of range each time they tried to focus on

him. Finally, with a grand gesture of childish

petulance, he flung out a dramatic arm and demanded the TV

lights should be shut off. He pulled the audience in

behind as he warmed to the role of the star punk giving

the finger to the old folks' medium. A storm of

catcalls and booing broke out. The lights were finally

extingished, and the rest of the film had to be shot in murky

half darkness.

During the second performance Morrison went a stage further. He

actually turned on the audience, interrupting the music with a

stream of random obsenities until it seemed that he produced what he

considered a postive reaction from the crowd. Once that was

achieved, he got back to business as usual. It was then

that the idea first occured to me that there was

something inside Morrison that forced him to push any

relationship to the ultimate. With both individuals and

audience he appeared to need to see how much they could

take. To define, by practical experiment, how much

abuse anyone would put up with before they ceased to

adore him. It was this willingness to go to the limit

that set Morrison apart from the commond herd of

posing, macho rock frontmen. It also created what was

possibly the greatest problem. As he discovered the

depth's of public masochism, just how much abuse these

people were willing to accept without revolting, he

became disgusted.

The second time I saw Jim Morrison it became

clear that his major victim was himself. It was

backstage at the Isle Of Wight Festival. He looked a mess.

A full beard and a cossack style smock couldn't

disguise the fact that he was grossly overweight. He had

been herded into a corner by John Sebastian and was

clutching a brandy, grunting responses, and looking for a

way to escape the tie-dyed collection of platitudes

as Sebastian gushed on about how "far out it all

was." Morrison looked desperate. Not just to get away

from the current situation. He seemed to have the

desperation of someone who knows his control is slipping

away.

The feeling was reinforced when he came out on the

stage. He was a shamling parody of himself. It was as

though he knew his performance wasn't worthy of the huge

crowds ritual adulation, that if they applauded so

easily their devotion could only be worthy of

contempt.

Over the years the memory becomes shaky. I can't quite

remember if Jimi Hendrix followed the Doors or the Doors

followed Hendrix. I was certainly drunk. Two things are

clear, however, they both played during the evening,

when the campfires of that particularily strife-torn

festival blazed across the hillside. They both play badly,

by their own standards, and they both seemed

sickened when the crowd received a medicore set as though

it was a triumph. In a matter of months, both men

were dead.

JAMES JAMES MORRISON MORRISON

COMMONLY KNOW AS JIM.

In the Jim Morrison Story, whom

would they get to play Jim as a boy? Whom for that

matter would they get to play Jim as a man? In the

magazine story there is hardly enough space for the

interviews with old school chums. That has o be left to He

Who Writes The Book. The Morrison early life has to

be presented as one of those continous dissolve

montages, like the News on the March sequence from "Citizen

Kane." No sooner has one scene appeared before it

dissolves for the next.

It's a boy, Mrs. Morrison, it's

a boy. The baby cradled by proud parents, mother

adoring, father dignified by gold braid. The child grows

into a sensitive, large eyed Freddy Bartholomew kind

of brat with dark curly hair. We see him playing

baseball, running through the fields. The picture darkens.

He gazes pensively at the rain on the window. Fights

with father, confrontation, running again, this time

through the rain. This isn't joy, now it's

flight.