Post by TheWallsScreamedPoetry on Jun 22, 2011 12:57:31 GMT

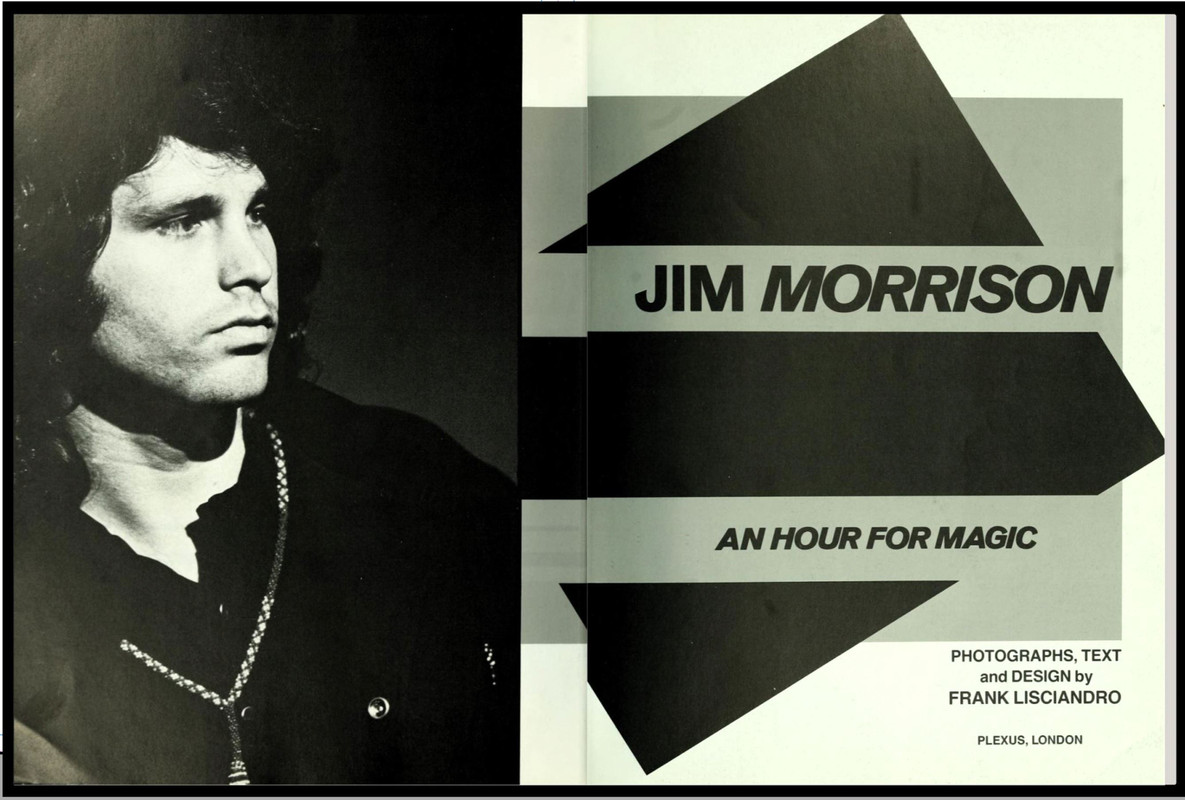

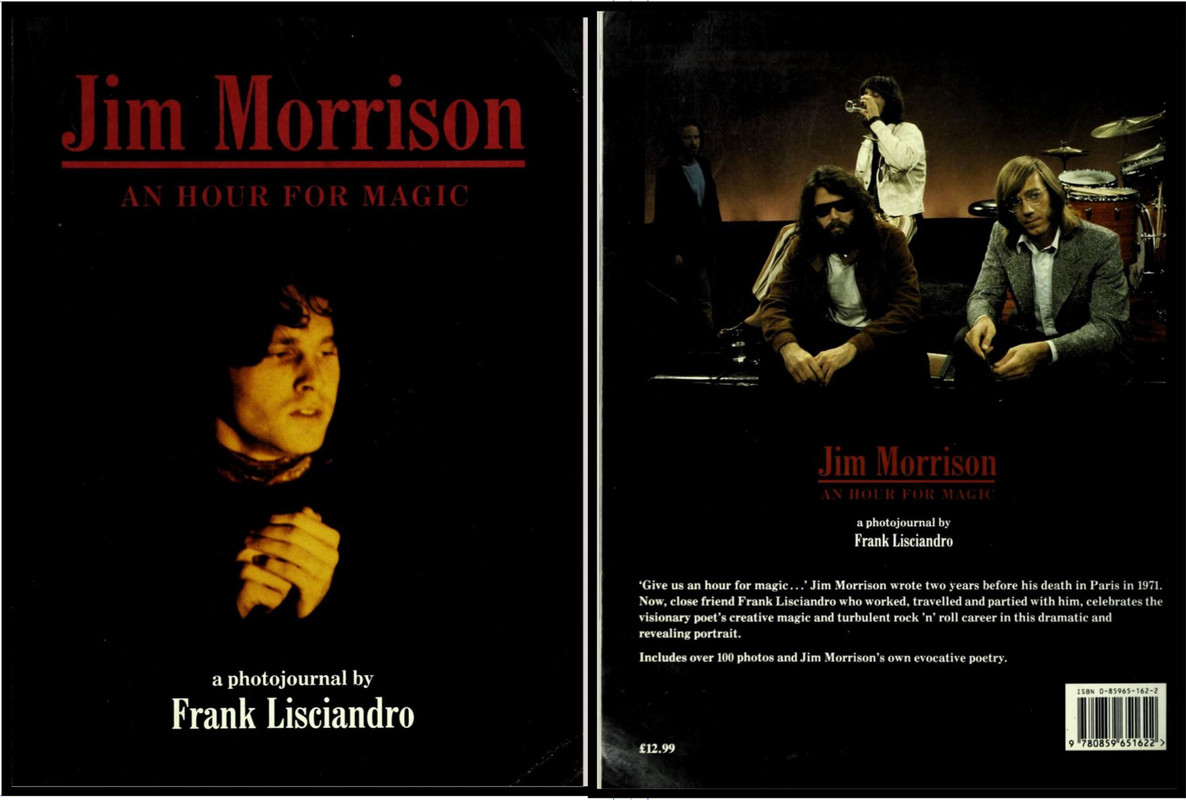

Jim Morrison: An Hour For Magic

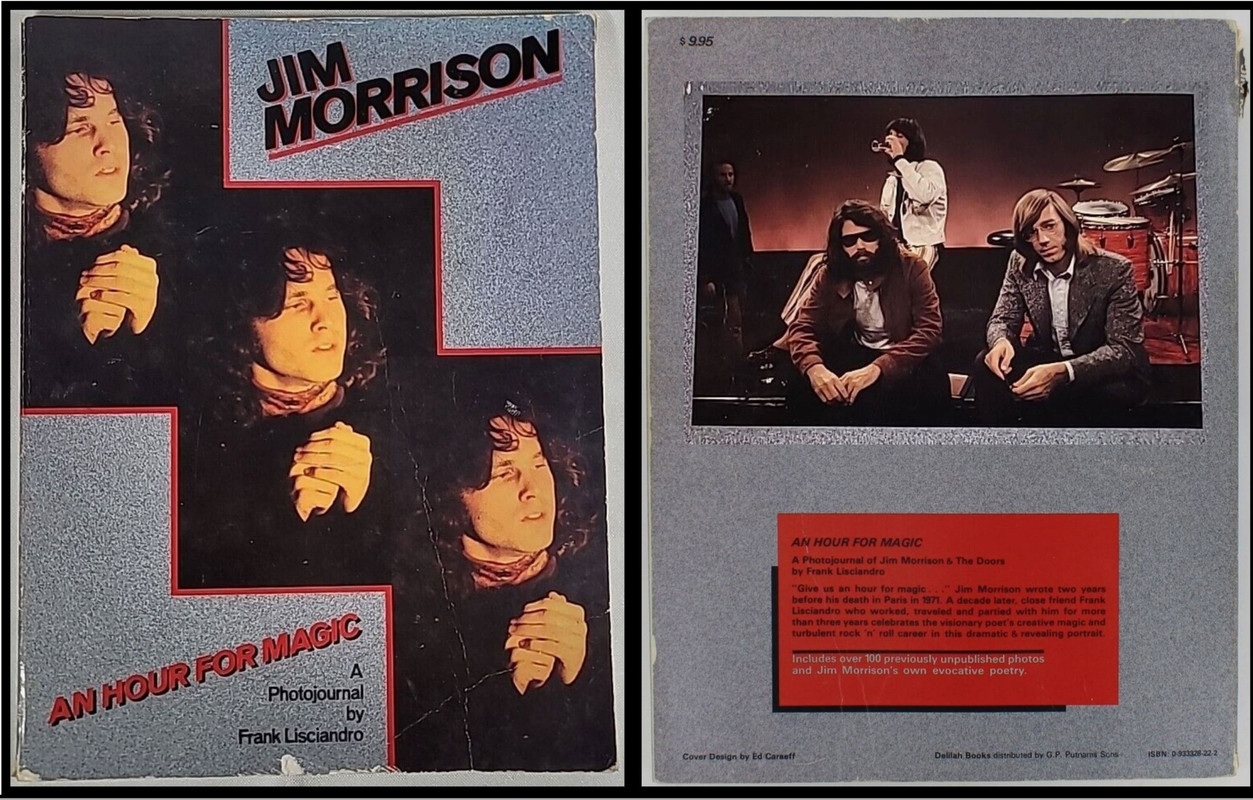

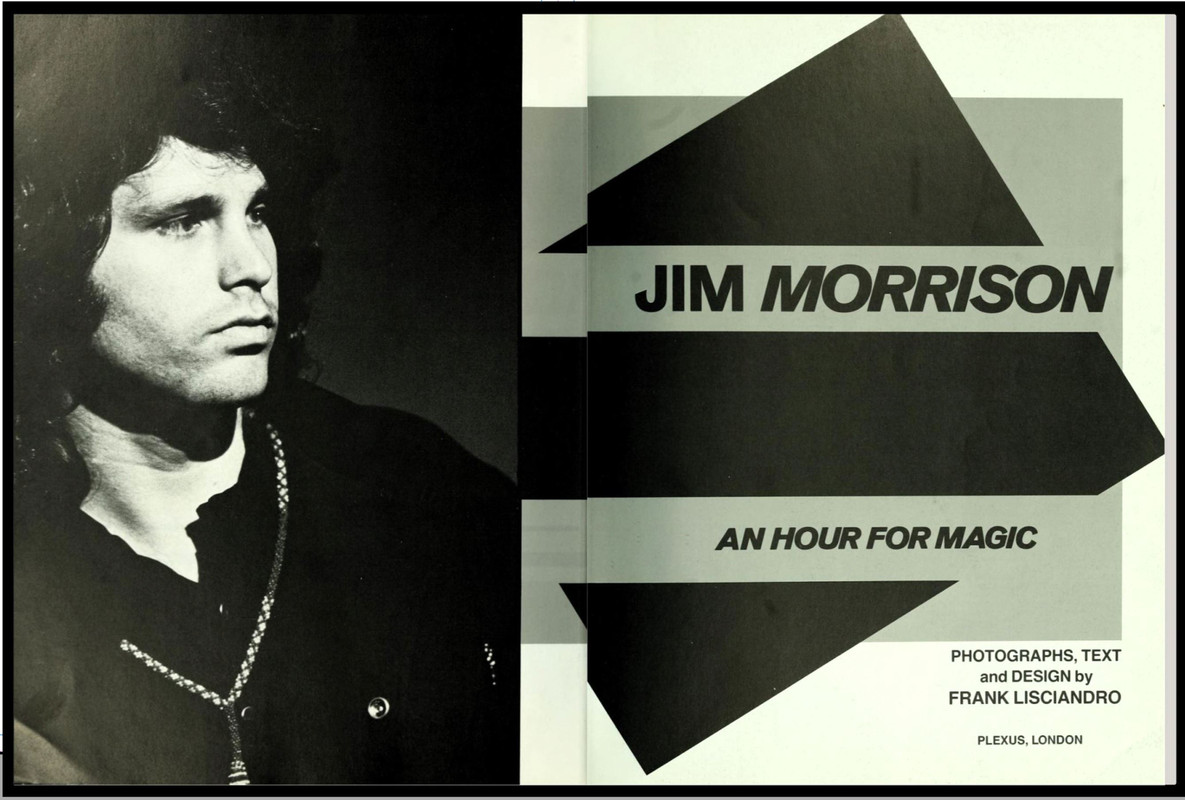

"By the time he left for Paris in March of 1971", Jim Morrison: An Hour for Magic tells us, "the friends he could depend on numbered less than ten." For a rock personality of Morrison's magnitude this sounds rather an optimistic estimate, but one has to remember it included this tome's author, Frank Lisciandro – a film school acquaintance from UCLA.

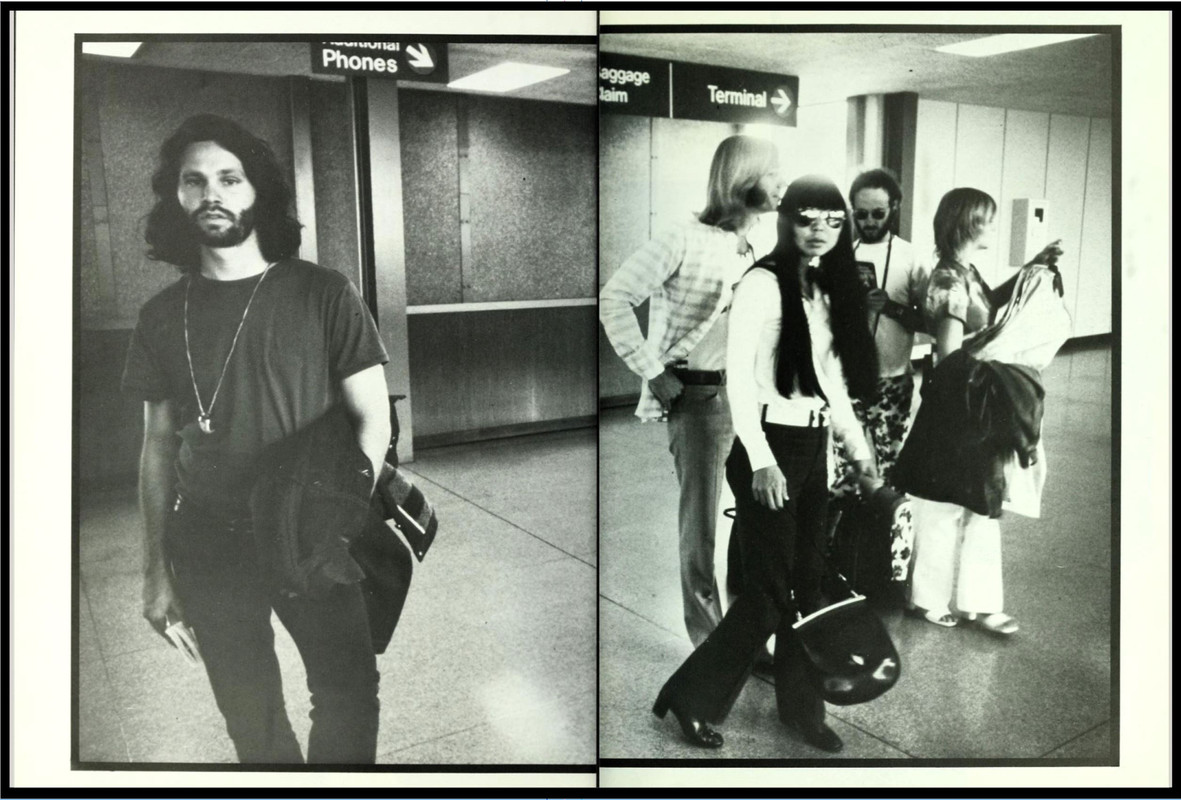

Lisciandro quit his job with "a prestigious educational/documentary film company" to try his hand at editing Morrison's Feast Of Friends project. He and his employer soon "traveled, worked and hung out together" (Lisciandro's spouse Kathy served as Jim's secretary for a period), and Lisciandro was in on much of Morrison's superstardom.

In Danny Sugerman and Jerry Hopkins' No One Gets Out Alive (which has sold four million copies so far) he is mentioned as one of a circle of JM's friends Morrison's common-law wife Pamela Courson 'particularly disliked' for their influence on her inamorata.

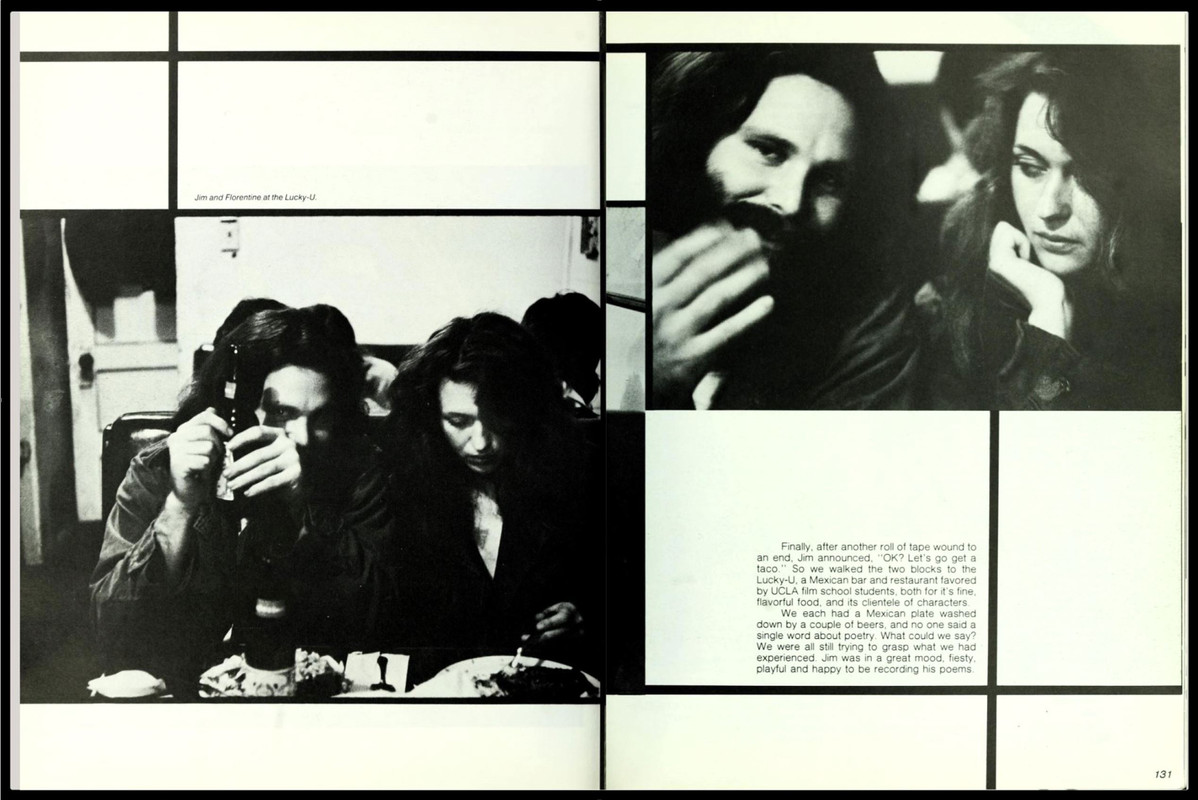

Whatever failing Lisciandro did or did not possess as a friend, the book he's spliced together from his Morrison exclusives (equal parts apologia, photos and poetry – some previously unpublished) epitomizes the true horror at the heart of rock superstardom: voyeurism too vacant to even bounce back an idea or two to the object of its attentions.

To Lisciandro – as to practically every 'friend' Morrison seems to have suffered/who suffered him, JM was "a shaman, a wizard, a sorcerer, a magician, a medicine man, a witch doctor, an enchanter, and a Dionysian reveller."

"For a long time," Lisciandro pontificates solemnly at one point, "my logical, pragmatic mind kept asking: how can an American-born son of a Navy Admiral of Scottish Irish heritage transform himself into a primitive sorcerer?" Indeed.

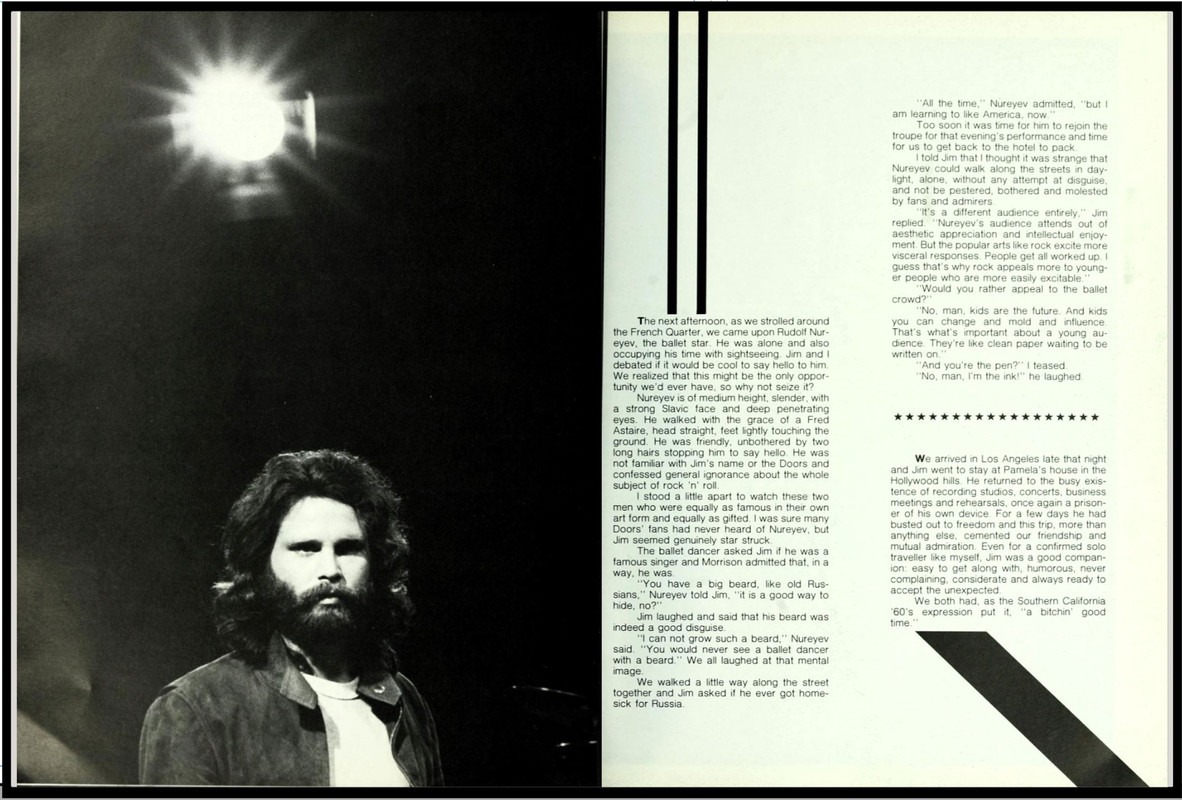

Lisciandro's 'logical, pragmatic',assessment of the reasons Morrison soon felt the need to hide behind a mountain man's growth of beard and hair, and an inability to shed his unsightly 40lb of extra flab was that "Jim changed on the outside because his mind was evolving into new levels of awareness." (One almost expects to read that he was perfecting a Method approach to audition as the Chivas Regal poster boy).

This new decade's gigantic exhumation of Morrison my have hopelessly obscured any chances of seeing what we really lost when he died an untimely death. But one thing has become increasingly certain: the money, mobility and celebrity he so avidly embarrassed brought him everything except a fellow mind which could accurately, honestly assess and advise on his actual personal potential. Someone who might just have said, 'Look Jim, the rhythms in this poetry you're trying to pioneer are going the same way as alcohol and self-consciousness are taking your stage show'.

None of Morrison's friends, though, knew what 'poets' actually did (and Morrison's 'real poet' buddies like playwright Michael McClure, who contributes a bit of writing to Lisciandro's book, were too rock-blinded to do more than go ga-ga at the endless opportunities Mr Mojo enjoyed for self-indulgence).

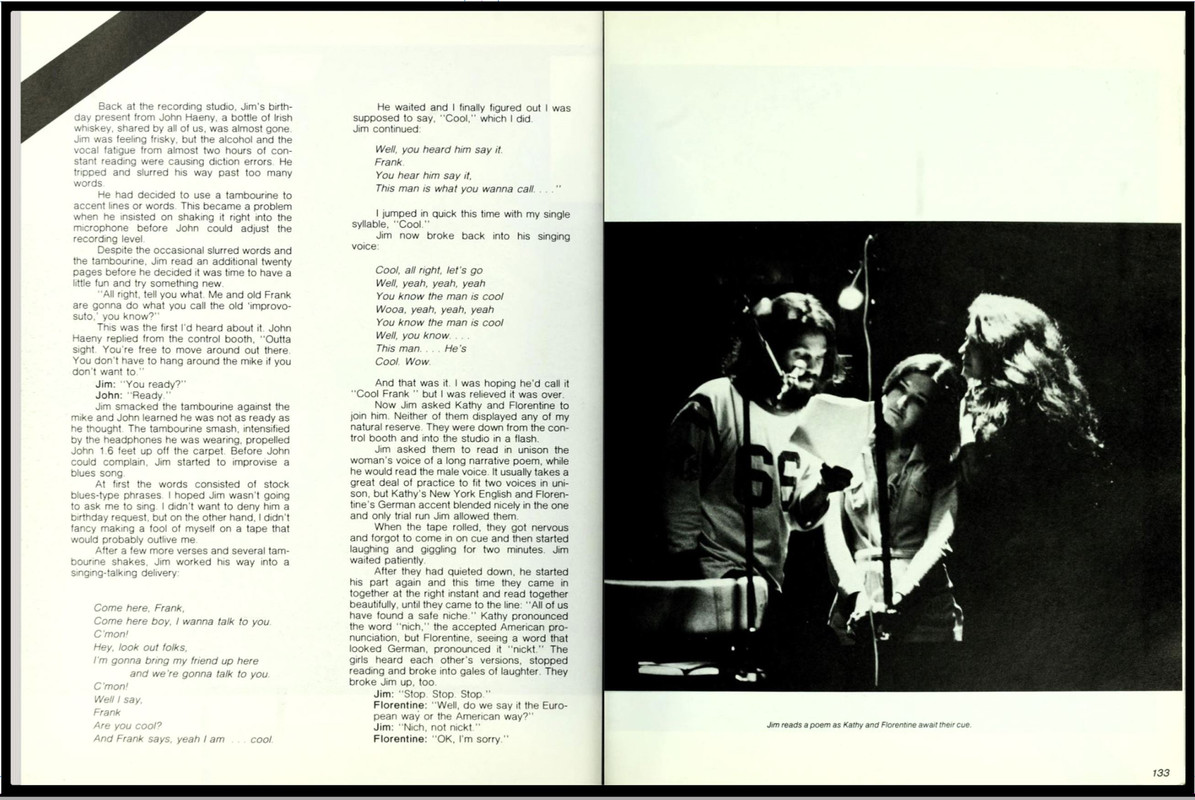

Like Lisciandro – who relates how paralyzed by sheer terror he felt when JM tried to involve him in a bit of improvisation in a studio during a birthday party – they were simply overwhelmed by the sort of 'personality' who could pop up during a hungover breakfast, replace their bacon-and-eggs with a more stylish Ramos Gin Fizz, and spirit them away for a spontaneous 500-mile road trip to New Orleans.

"Almost all his friends," says the author in a particularly creepy passage, "saw Jim's lifestyle as self-destructive. But looking in the light of the ancient poet/oracle tradition (sic), his life-style could be called self-instructive." Except that such ephipanies certainly pay off too late for the artist in question; they're profitable only for the posthumous pictures-and-quotes vultures.

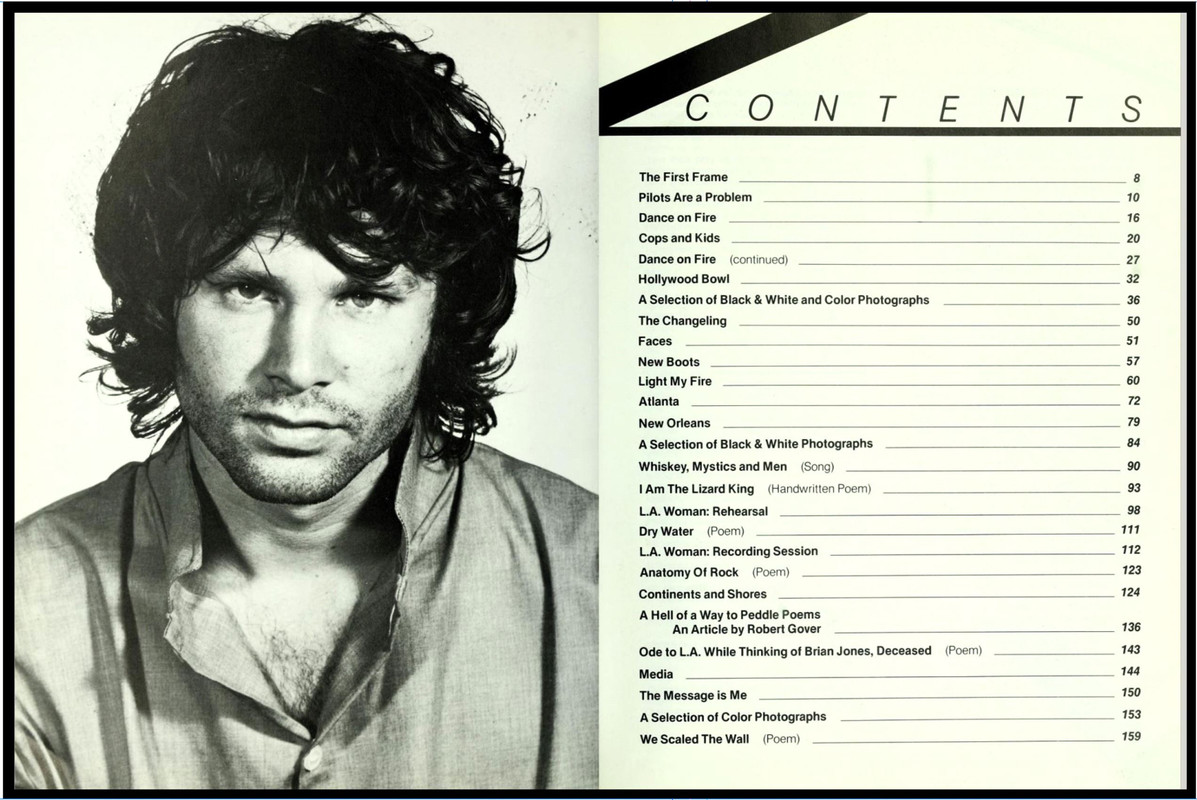

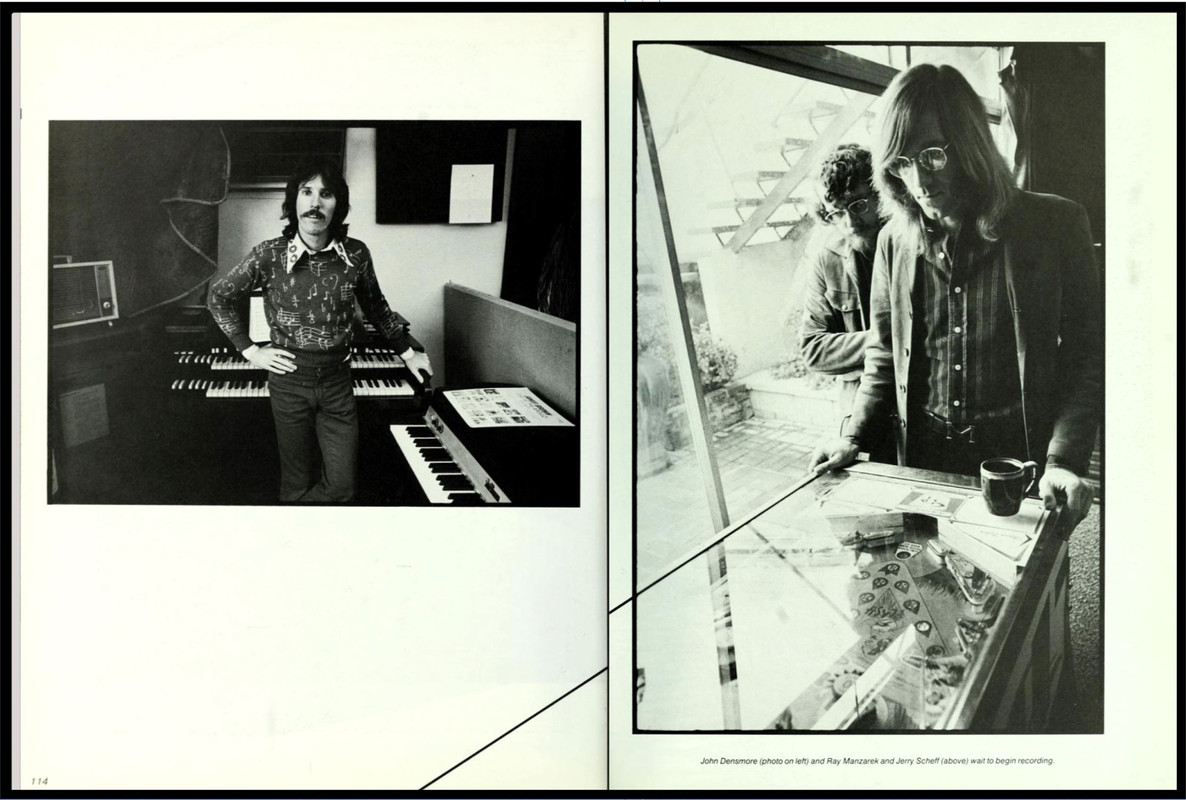

Frank Lisciandro's Jim Morrison: An Hour For Magic is published by Eel Pie at £5.25 and includes – for Morrison maniacs – plenty of new pix as well as the following poems: 'I Am the Lizard King' (handwritten), 'Dry Water', 'Anatomy of Rock', 'We Scaled the Wall', and 'Ode to LA While Thinking of Brian Jones, Deceased'.

Frank Lisciandro edited Morrison's 40-minute film Feast of Friends and with Morrison and Paul Ferrara, made the 50-minute HWY – a 35-mm colour sync-sound movie.

Cynthia Rose, NME, 12 June 1982

"By the time he left for Paris in March of 1971", Jim Morrison: An Hour for Magic tells us, "the friends he could depend on numbered less than ten." For a rock personality of Morrison's magnitude this sounds rather an optimistic estimate, but one has to remember it included this tome's author, Frank Lisciandro – a film school acquaintance from UCLA.

Lisciandro quit his job with "a prestigious educational/documentary film company" to try his hand at editing Morrison's Feast Of Friends project. He and his employer soon "traveled, worked and hung out together" (Lisciandro's spouse Kathy served as Jim's secretary for a period), and Lisciandro was in on much of Morrison's superstardom.

In Danny Sugerman and Jerry Hopkins' No One Gets Out Alive (which has sold four million copies so far) he is mentioned as one of a circle of JM's friends Morrison's common-law wife Pamela Courson 'particularly disliked' for their influence on her inamorata.

Whatever failing Lisciandro did or did not possess as a friend, the book he's spliced together from his Morrison exclusives (equal parts apologia, photos and poetry – some previously unpublished) epitomizes the true horror at the heart of rock superstardom: voyeurism too vacant to even bounce back an idea or two to the object of its attentions.

To Lisciandro – as to practically every 'friend' Morrison seems to have suffered/who suffered him, JM was "a shaman, a wizard, a sorcerer, a magician, a medicine man, a witch doctor, an enchanter, and a Dionysian reveller."

"For a long time," Lisciandro pontificates solemnly at one point, "my logical, pragmatic mind kept asking: how can an American-born son of a Navy Admiral of Scottish Irish heritage transform himself into a primitive sorcerer?" Indeed.

Lisciandro's 'logical, pragmatic',assessment of the reasons Morrison soon felt the need to hide behind a mountain man's growth of beard and hair, and an inability to shed his unsightly 40lb of extra flab was that "Jim changed on the outside because his mind was evolving into new levels of awareness." (One almost expects to read that he was perfecting a Method approach to audition as the Chivas Regal poster boy).

This new decade's gigantic exhumation of Morrison my have hopelessly obscured any chances of seeing what we really lost when he died an untimely death. But one thing has become increasingly certain: the money, mobility and celebrity he so avidly embarrassed brought him everything except a fellow mind which could accurately, honestly assess and advise on his actual personal potential. Someone who might just have said, 'Look Jim, the rhythms in this poetry you're trying to pioneer are going the same way as alcohol and self-consciousness are taking your stage show'.

None of Morrison's friends, though, knew what 'poets' actually did (and Morrison's 'real poet' buddies like playwright Michael McClure, who contributes a bit of writing to Lisciandro's book, were too rock-blinded to do more than go ga-ga at the endless opportunities Mr Mojo enjoyed for self-indulgence).

Like Lisciandro – who relates how paralyzed by sheer terror he felt when JM tried to involve him in a bit of improvisation in a studio during a birthday party – they were simply overwhelmed by the sort of 'personality' who could pop up during a hungover breakfast, replace their bacon-and-eggs with a more stylish Ramos Gin Fizz, and spirit them away for a spontaneous 500-mile road trip to New Orleans.

"Almost all his friends," says the author in a particularly creepy passage, "saw Jim's lifestyle as self-destructive. But looking in the light of the ancient poet/oracle tradition (sic), his life-style could be called self-instructive." Except that such ephipanies certainly pay off too late for the artist in question; they're profitable only for the posthumous pictures-and-quotes vultures.

Frank Lisciandro's Jim Morrison: An Hour For Magic is published by Eel Pie at £5.25 and includes – for Morrison maniacs – plenty of new pix as well as the following poems: 'I Am the Lizard King' (handwritten), 'Dry Water', 'Anatomy of Rock', 'We Scaled the Wall', and 'Ode to LA While Thinking of Brian Jones, Deceased'.

Frank Lisciandro edited Morrison's 40-minute film Feast of Friends and with Morrison and Paul Ferrara, made the 50-minute HWY – a 35-mm colour sync-sound movie.

Cynthia Rose, NME, 12 June 1982