Post by TheWallsScreamedPoetry on Sept 22, 2022 10:46:59 GMT

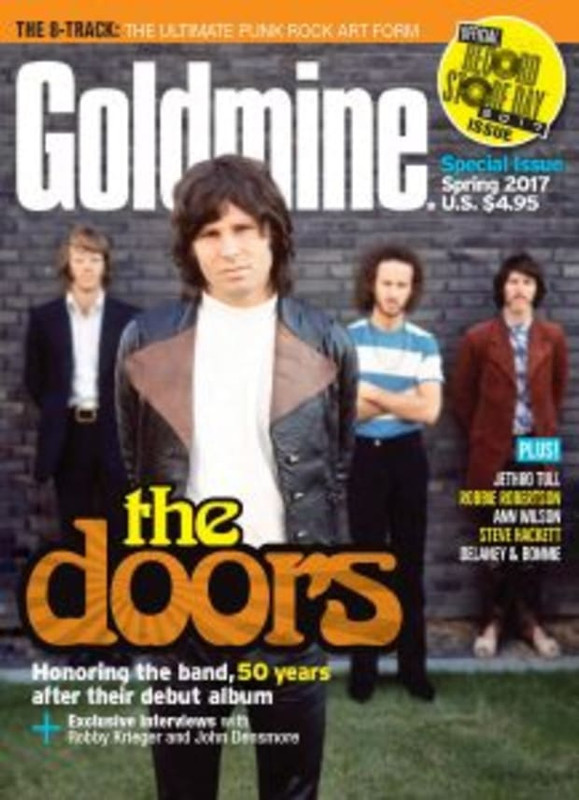

This article ran in the special Spring 2017 issue of Goldmine (above), the Record Store Day issue.

As Ray Manzarek colorfully, eloquently and frequently recalled through the years, The Doors were born in the summer of 1965 when the keyboardist encountered Jim Morrison, a fellow UCLA film school graduate, on the beach in Los Angeles.

While making small talk, Morrison revealed he’d written some songs. A curious Manzarek coaxed him into singing a few. Morrison, with his eyes closed and clutching handfuls of sand, launched into a tune titled “Moonlight Drive.”

More than half a century later, drummer John Densmore remembers “Moonlight Drive” also being the first song he, Morrison, Manzarek and guitarist Robby Krieger played together as The Doors. Yet when it came time to assemble the group’s first album, “Moonlight Drive” did not make the final cut.

“The words were fabulous,” Densmore adds, “but it just didn’t come together until later.”

The band had plenty of material to choose from — enough for at least two albums, according to Densmore. The Doors eventually selected nine other originals, plus two covers, for their self-titled debut on Elektra Records.

Working with producer Paul A. Rothchild and engineer Bruce Botnick at L.A.’s Sunset Sound, The Doors recorded the entire album in just six days during the summer of 1966. Rothchild mixed the album in Manhattan that fall, with the band helping out in the afternoons before performing at the hip Ondine club, part of a long residency set up by the producer.

Featuring elements of classical, jazz and blues, “The Doors” was a distinct and daring debut for a rock group — and Elektra knew it. As part of its marketing efforts for the band and the album, the label proclaimed in print, “The Doors will be the most talked-of new group in 1967. Theirs is an album of overwhelming intensity; a veritable tidal wave of pungent electric sound that heralds a major breakthrough in contemporary music.”

“The Doors” arrived in stores on Jan. 4, 1967, and thanks in large part to “Light My Fire,” which reached No. 1 on the Hot 100 that summer, the album spent 100-plus weeks on the Billboard 200 chart, peaking at No. 2. (It was thwarted from the top spot by The Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.”) Certified quadruple platinum by the RIAA, “The Doors” remains the most successful of the band’s studio efforts featuring the charismatic and controversial Morrison, with “Light My Fire,” “Break on Through (To the Other Side)” and other songs still receiving their share of airplay today on rock radio stations across America.

So far, 2017 is shaping up to be a big year for The Doors. On Jan. 4, Densmore and Krieger, the only surviving members of the band, attended a ceremony in L.A.’s Venice neighborhood, where the fledgling group was formed. (Morrison died in 1971 of reported heart failure; Manzarek died in 2013 from bile duct cancer.) According to “L.A. Weekly,” an estimated 500 people gathered at the intersection of Pacific and Windward for the brief event, during which L.A. City Councilmember Mike Bonin officially designated Jan. 4 to forever be known in Los Angeles as “Day of The Doors.”

In March, Rhino Records commemorated the 50th anniversary of the first Doors album with a deluxe edition packaged in a hardcover book. It contains three compact discs: The first disc is a remastered version of the album’s original stereo mix, the second has the original mono mix (released for the first time on CD), and the third contains eight songs from a concert that was recorded at The Matrix in San Francisco about two months after Elektra released “The Doors.” The deluxe edition also includes a vinyl version of the album’s mono mix, as well as rare and previously unseen photos, plus extensive liner notes by longtime “Rolling Stone” writer David Fricke.

“I was hoping we would last a decade and pay the rent,” says Densmore. “And here we are, still talking about the first album 50 years later.”

As it turns out, Densmore and Krieger still have lots of interesting things to say.

GOLDMINE: Not long after The Doors parted ways with Columbia Records, without ever recording for that label, the band signed with Elektra. What in particular about Elektra made it the right company for you guys?

JOHN DENSMORE: Well, it was a small boutique label that had a bunch of artists that we respected, such as Paul Butterfield. And Judy Collins was covering then-unknown Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen. It was just a very hip, small folk label, and we could actually talk to the president (Jac Holzman). It wasn’t a giant corporation.

ROBBY KRIEGER: They had just signed Love and had a good release with them. They were kind of our heroes in L.A., and we figured if they’re good enough for Love, they’re good enough for us. (laughs) I always loved everything on the label. I probably had three-quarters of their releases in my collection, so it was pretty cool to be on Elektra.

GM: What were your first impressions of Paul A. Rothchild and Bruce Botnick as people and as studio professionals?

JD: Paul knew he was a good producer, and he taught us how to make records. And Bruce already had a great (track record). We all had a great time hanging out. Paul was the fifth Door, and Bruce was the sixth.

RK: I had never met a producer or an engineer before, really. The thing about Paul was he had produced a lot of records that I really loved, including Paul Butterfield. It was amazing that we got him to be our producer because he had worked on half of my favorite records.

Paul was kind of a New York guy, and we really didn’t know many people like that. He was this high-energy guy. He was very positive and super-hip. We immediately bonded with him. And Bruce was cool (and experienced), too. We were kind of in awe of those guys.

GM: “Hello, I Love You” and “You Make Me Real,” among other Doors originals, were part of the band’s early repertoire, but they didn’t make the cut for the first album. Talk about what went into selecting the 11 songs that are on the debut album.

JD: We worked on “Hello, I Love You,” and I knew — everybody knew — that those lyrics were great. Jim was so poetic. But the arrangement did not coalesce until the third album.

RK: We had 20 songs or more ready to record. We thought that a lot of them would be hit records. We did record a lot of them; we did a version of “Moonlight Drive” — in fact, that was one of the first things we recorded at Sunset Sound. But it just didn’t sound like a single and didn’t have that zip to it, so we thought, “Well, let’s save this one for later. We’ll try and do it again for the next album.” And the same thing for “Hello, I Love You.”

GM: As for “Alabama Song (Whisky Bar)” and “Back Door Man,” were there other cover songs in contention for the first album, or were they definitive choices?

RK: Those two were pretty much “for sure.” We did do other covers: “Gloria” (by Them), some Wilson Pickett stuff and James Brown. But those were the ones that were our favorites.

GM: Robby, there’s an element to the “Light My Fire” backstory that needs clarification. Oliver Stone’s 1991 movie about The Doors shows you, Jim and John stepping outside during a rehearsal, and in short order, Ray comes up with the song’s instrumental introduction. And in his 1998 autobiography, Ray confirmed what happened in that scene, also mentioning he was the one who felt the song needed an intro. But last year in a “Song Stories” segment for Reverb.com, you shared a very different recollection about the introduction that involved Paul Rothchild. Can you set the record straight?

RK: That intro was not an intro at first. Before we recorded “Light My Fire,” that part was in the middle of the song. It was the way that we got out of the instrumental and back into the song. It was really Paul Rothchild’s idea to use it as an intro when we recorded it.

GM: And to use it as the outro, too, correct?

RK: And as the outro — right. Or maybe we all said, “Hey, that really works. Let’s do it again and put it at the end, too.”

GM: So for years, Ray was putting out this story that seemed like something that could have come out of one of his student films at UCLA.

RK: (laughs) In Ray’s mind, I’m sure he was right. Ray did come up with the Bach part over those chords. If you want to hear the original (arrangement), it’s on the Matrix tapes. “Light My Fire” does not start with that intro.

GM: Not only does the Matrix recording not have the signature intro, what is now the intro appears between the first and second verses, as well as when you’re coming out of the solos, as you told Reverb.

RK: It came after the first verse, too? Maybe you’re right. I knew it was around there somewhere. (laughs)

Robby Krieger’s Matrix Memories

GM: John, you told CBS-TV correspondent Anthony Mason in 2013 that you heard rhythm when you read Jim’s lyrics for “Break on Through (To the Other Side).” Did you instantly hear a bossa nova beat, or did arriving at that distinctive groove involve working through a variety of rhythmic styles and tempos first?

JD: Good question. No, I didn’t hear bossa nova instantly. I heard rhythm in the words, though: “You know the day destroys the night/Night divides the day/Tried to run, tried to hide/break on through to the other side.” So I was excited to explore what rhythms I might come up with. I heard movement. At the time, “The Girl From Ipanema” was a big hit. I was fooling around with that, and then I experimented with the rhythm and made it different for “Break on Through.”

The Doors circa 1967. © Doors Property, LLC. photo by Bobby Klein.

The Doors circa 1967. © Doors Property, LLC. photo by Bobby Klein.

GM: When it came to finalizing the track order, was that a band-only decision, or did Elektra personnel or others in the group’s inner circle also have a say?

JD: It was mostly the band, but Rothchild had strong opinions on things. We put in the time and painstakingly programmed it for someone sitting down for (a complete listening experience).

GM: Was it a difficult, drawn-out process?

RK: Not really. It wasn’t that much different from the way we played a set. A lot of times we would start with “Break on Through” and end with “The End.” “Light My Fire” normally would have been right before “The End,” but on the album, we ended the first side with “Light My Fire.”

GM: Whose idea was it to have Jim’s face dominate the album’s front cover?

JD: (laughs) All of a sudden it just showed up (that way). The wonderful photographer Guy Webster did the photo shoot with all of us, and then somebody — maybe Bill Harvey, the art director at Elektra — put it together with Jim’s face real large. I was jealous, and then I thought, “Well, Jim looks like Michelangelo’s David (sculpture)…”

RK: We were taken aback, but nobody complained. There was fallout from that: For the second album (“Strange Days”), Jim especially insisted that none of our pictures be on the front of the album.

GM: John, in your 1990 autobiography, “Riders on the Storm,” you wrote that each member of the band was given 10 copies of the first Doors album. Do you remember what you did with them?

JD: Oh, wow — no. (laughs) I probably handed them all out to family and friends.

GM: Robby, do you recall what you did with your allotment?

RK: Oh, boy, I sure don’t. I might still have one or two.

GM: Long before music videos became the norm, The Doors made a sparsely lit promo clip for “Break on Through.” Did Jim and Ray get to use any of their film school training for the shoot?

JD: That was shot by Mark Abramson; he was the film guy at Elektra.

GM: Robby, it appears as though the tie you’re wearing in the video is the same as the one you’re wearing on the cover of the first album. Were the video and cover photo done on the same day?

RK: They were done in the same period of time, while we were back in New York. I got that tie because (it’s like the one) that Miles Davis is wearing on his album cover for “My Funny Valentine.”

GM: In the photos of the band next to Elektra’s “Break on through with an electrifying album” billboard on Sunset Boulevard, everyone appears to be relaxed, taking the whole first-album experience in stride. What was going through your mind at that time?

RK: We were pretty proud of having our own billboard on the Sunset Strip. We loved it. We lived right near there, so every day, we’d drive by and say, “Hey, that’s us.” (laughs)

JD: Well, we were kind of nervous because it was so high. (laughs) We were tripping. It was odd; it was weird (being up there). That’s another wonderful thing Jac Holzman did: No one until then had ever used billboards to advertise music. I remember a prominent local newscaster interviewing us while it was being put up: “Why are you doing this? You can’t hear a billboard.” And it turned out to be a (success because sales) went through the roof, thanks to Jac’s vision on how to market music in a new way.